A slowing economy by design to reset the trajectory of the American economy.

That is what I think the goal of the new administration is at this time. US GDP projections have been adjusted to an overall +1.5% this year, down from +2.8%, and after a negative first quarter GDP announcement, driven by the heavy import/export imbalance, GDP is expected to turn positive for the remaining 3 quarters. Q1 earnings releases have been mostly positive as well.

Inflation cooled slightly, the labor market is hanging in there, consumer consumption has remained steady, and pretty much all contributors to GDP for the first quarter remained unchanged.

Industrial manufacturing is the biggest cause for concern, which does not bode well for the domestic truckload market. But, as we will dive into further, the US manufacturing sector has been stagnant for years. US Manufacturing has not been a major contributor to economic growth. In fact, there has been zero growth in US manufacturing for 25 years.

That little tidbit honestly shocked me, as Matthew Klein put it “That kind of stagnation is unprecedented outside of the Great Depression.”

So while a downturn in manufacturing activity in this period of uncertainty is definitely a negative thing, it’s not like we are talking about slowing down a sector that has been propping up US economic growth in recent years.

As I see it, the current goal is to reduce the US’s dependence on China, while actually creating more lucrative and politically beneficial partnerships with other nations. Yes, Trump’s sudden and seemingly bullyish tactics to force everyone to the negotiation tables have been widely criticized, but early reports of the deal we are finalizing with Britain might be the beginning of proof that the strategy could yet still have some effectiveness.

In earnings calls, companies discussed their already previously ongoing efforts to become less reliant on China for sourcing, and instead engage with other new trading partners, partners that are currently at the tables with the US right now. China’s own economy is in no position to increase domestic demand for their products, and if the US strikes deals with other companies, that business may never shift back. There are some serious downsides and risks growing for China to not negotiate. And then, simply put, the US seems okay with sacrificing many of the cheap goods that were entering the US from China that have fueled what has been called “overconsumption” trends in the US.

I do not believe that the end goal is a full revival of domestic manufacturing where most of our goods are produced here. I believe the goal is to resume a steady growth of products being manufactured here in the US that has been stagnant for 25 years, and then to start sourcing our goods from countries where we have increased our mutually beneficial trade agreements. Partnerships that allow us more income from slightly elevated tariff levels, but also deals where US imports are increased to those trading partners as well. We shall see.

Some sources are pricing in 3 FED rate cuts still this year, with the first coming in July. If some trade deal details start to surface that are beneficial for the US, the labor market at least remains steady, the FED makes a minimal rate cut, inflation proves to be transitory (yeah that word is backkkk), GDP flips back positive in Q2, earnings calls in Q2 remain in positive territory, and the Tax Deal now being proposed is passed promising corporate tax cuts and other individual tax cuts, I think there is a case for the American economy to cool just enough, to adjust to another new, and maybe healthier normal, prior to resuming growth into 2026.

That’s a lot of forward looking there, so now I’ll walk you through what I was reading this month to start to formulate forward looking opinions. At the end of the day though, I’m seeing few short term reasons to expect any type of stimulus for the domestic full truckload market. At this point, I think we need to be happy if we can prevent any further deterioration.

Manufacturing is in a bad spot. April’s PMI data showed minimal improvement in New Orders and is still in contraction territory.

Jason Miller says “Hopefully we will have some clarity on tariffs emerging over the coming weeks to make a more informed prediction for the coming months.”

As of right now, it seems that uncertainty has caused the manufacturing space to pause as it awaits clarity needed to make the right decisions. If we can start to get more deals finalized in the coming weeks, perhaps the pause can begin to lift.

Texas manufacturing seems to be getting hit exceptionally hard, and it has Texas business leaders calling on the FED to begin cutting interest rates.

Phil Rosen covered the recent Dallas Fed data releases.

“The Texas manufacturing sector is calling for the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. While factory activity in the nation’s second-largest economy held firm in April, other measures of underlying hard and soft data deteriorated dramatically, according to the Dallas Fed’s latest regional report. New Orders Index plunged 20 points to -20.0, Shipments Index fell to -5.5, entering negative territory the first time this year, General Business Activity Index fell to its lowest since May 2020, Company Outlook Index dropped to a new post-pandemic low, Outlook Uncertainty Index spiked 11 points to 47.1. Taken together, the numbers point to a manufacturing hub buckling under tighter financial conditions and mounting tariff concerns. “There is too much uncertainty, including a possible recession,” one Texas executive put it, according to the survey. “Interest rates are too high. The Federal Reserve always seems to be late for their own party.”

Before moving on from manufacturing to inflation and interest rates, I want to spend some time on the overall US manufacturing landscape. Matthew Klein wrote a brief and informative piece on this that I highly recommend you read.

Since 2000, American manufacturers have slashed investment in domestic capacity, although it is possible to see a turn around 2021-2022. (Not coincidentally, the time when the government began actively encouraging more U.S. manufacturing investment.) The bizarre result was that surging domestic demand for manufactured goods had almost no impact on domestic supply for the past 25 years.Reported manufacturing labor productivity continued to rise in the early 2000s thanks in large part to the one-off gains from mass layoffs, but since 2007 there have been no increases in real output per worker. Again, this is unprecedented. The only thing that comes close is the post-WWII reconfiguration of production from wartime to peacetime.

And…

These are serious problems that threaten both American prosperity and U.S. national security. We live in the physical world, and historically, economy-wide productivity gains and technological innovations have been disproportionately attributable to manufacturing improvements rather than the services sector. Yet some people choose to dismiss all this, instead claiming that manufacturing is irrelevant because the share of workers in manufacturing jobs has been in secular decline for decades. Of course, that is exactly what one would expect if manufacturing tends to have faster productivity gains than the rest of the economy! The chart below is both misleading and irrelevant for most current policy debates. I am including it so that you know to be wary of anyone using versions of this chart in discussions of anything other than relative labor productivity trends.

In summary, when the US started to aggressively invest in Asian manufacturing outsourcing during the Asian financial crisis (when it was cheap to do so), we stopped growth in domestic manufacturing. Even though US demand for goods has rapidly increased, there has been NO increase in domestic production. The argument does not need to be that everything be made in the US, but friends, something needs to be made in the US. The other argument is that even with automation there would still be steady job and production growth domestically, and we should be adopting as much automation as we can. Our utter lack of domestic production growth is not very indicative of an advanced economy.

Years ago now, the pandemic started waking up many countries to the risks of being overly dependent on China, and so we have seen more nearshoring and shifts to other trading partners, I expect the goal of these steep Chinese tariffs is to continue to drive investment out of China. And, I’m not convinced China can afford to let that happen. And I’m also not convinced that the goal is to negotiate down with China to resume business as usual, I think this is an intentional play to harm the Chinese economy as they become an increasingly more instigative global power with allies that consistently are unaligned with the US.

Matthew Klein also had an interesting piece on the Chinese economy, here is an excerpt to help better show why they may not be poised to play hardball for long:

The shift in investment from empty real estate and poorly-located infrastructure to additional manufacturing capacity might seem like a solution to the first problem, except that the additional manufacturing capacity only makes sense if demand rises fast enough—and that requires some combination of booming export markets and robust domestic consumption. (Neither of which seems likely at the moment.)

So now then, the case for the FED to begin cutting interest rates this summer. Consumer sentiment data, which I covered last month, has been terrible. And many corporations are citing uncertainty as a major challenge, despite positive Q1 earnings and many still holding an optimistic outlook. The way it seems to be shaping up, is that an interest rate cut would be like an economic morale booster. We likely won’t have full clarity on tariffs by the time the FED could cut interest rates in June or July. Which is precisely what many are urging them to do, and many are saying they are already going to be too reactionary. Business leaders, economists, journalists, and President Trump have all voiced a desire for the FED to cut rates.

But why do they hold them still? Inflation and labor markets, those are their two primary concerns. The FOMC kept the rates unchanged at 4.25%-4.50% this month.

Jan J. J. Groen seemed to hone in on what the FED may likely be thinking after their unwillingness to change rates at the May meeting. The FED said that the economy is actually still holding up and is in acceptable shape, therefore making a mistake that would allow inflation to begin increasing again is something they are not yet willing to risk.

“Given that the large-scale tariff hikes will likely more quickly impact inflation than the labor market, and that the already elevated inflation expectations could make this inflation impact more persistent, it’s very unlikely that the Fed will change policy rates this year or maybe not until year-end. But with a lot of easing in the perceived monetary policy stance due to a pickup in inflation expectations this will not be welcomed by Fed officials. The possible easing impact of these developments could make their job of anchoring inflation expectations harder, so at the very least FOMC officials, IMO, will want to guide rates to remain elevated by signaling persistently unchanged policy rates to counter this potential effect. So, overall developments in the economy right up to the eve of “Liberation Day” remain solid. However, survey-based inflation expectations have exhibited a broad-based and notably firming. Even if some surveys overstate the role of uncertainty, the broad-based rise in expectations signals heightened concern about inflation volatility. Disinflation is being discounted. Combined with underlying trends in the “hard” inflation data still pointing to a persistently above-2% pace of price increases, "looking through" inflationary tariff effects thus is becoming harder for the Fed— and depends on how much labor market weakness they’re prepared to tolerate.”

The labor market is not showing any major signs of weakness. But David Kelly argues that it might be flashing warning signs in the latest jobs data report. I’d consider this stance to be more cautionary than others right now, but the reasonings could prove to be solid if there are no further updates on tariff negotiations, corporate tax cuts, or FEd rate cuts in the coming months:

David explained his reasons for suggesting that the labor market may be less healthy than others suggest:

“First, the payroll report referred to the pay period that contained the 12th of April. This may have been too soon after the April 2nd tariff announcement for companies to react with increased layoffs or slower hiring. To that extent, the May jobs report, due out on June 6th, should provide a better reflection of the initial impact of tariff uncertainty on firm behavior. Second, revisions subtracted 58,000 jobs from the payroll gains of the prior two months. Third, April saw few disruptions to the labor market with just 5,000 workers involved in major strikes and unusually low numbers claiming an inability to work due to bad weather or illness. Fourth, while the unemployment rate was unchanged, the absolute number of people unemployed at 7.17 million was its highest since October 2021 and almost as high as the number of job openings, which fell from 7.48 million at the end of February to 7.19 million at the end of March. Finally, employment reacts to real GDP growth with a lag. As demand slows, firms are reluctant to fire workers right away, particularly when they had a hard time hiring them in the first place. However, if real GDP growth is essentially flat for the first three quarters of the year, (as we expect without a favorable resolution of the trade war or near-term fiscal stimulus), job growth could well turn negative over the next few months.”

David also wrote a brief update on the upcoming vote regarding the current tax proposal. House Speaker Mike Johnson is pushing for a vote on a major tax bill. It’s expected to extend the 2017 tax cuts and add new breaks, including cuts to corporate taxes and income taxes on tips, overtime, and Social Security. It may also bring back deductions for auto loan interest and state and local taxes. If passed this summer, lawmakers will decide how quickly to roll out the cuts. They could wait until 2026 or move faster if they’re worried about a recession. In other words it appears that the government is preparing for another lever to be pulled if needed, and needed may mean slow tariff negotiations, or no FED rate reductions.

Phil Rosen , who is joining me on the Meet Me For Coffee Podcast this coming Tuesday (link to register here), covered the thoughts of the Yardeni Research team on inflation and the FED rate cuts. Definitely taking a more urgent stance.

“Long-term inflation measures — including the difference between 10-year nominal and TIPS yields as well as swaps for the period five to ten years in the future — have sunk toward levels consistent with the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target,” the Yardeni Research team wrote in a note early Tuesday. As much as inflation risks have dominated headlines, growth is arguably the deeper risk. Should uncertain, up-and-down trade policy persist, the Fed won’t only have to bring rate cuts to the table, but they might have to act faster than anyone’s pricing in… It’s worth noting, too, that the reported March inflation data came in at 2.4% year-over-year, below the forecasted 2.6%, and saw its first month-over-month decline since May 2020.”

And here are some further resources on updated stances as of the last couple of weeks on the coming months.

Gregory Daco wrote in his Fed Pulse newsletter:

Overall, we believe incoming hard data overstates the economy’s resilience. The moderation in headline PCE inflation to 2.3% y/y in March, and in core PCE inflation to 2.6% y/y supports the case for cautious policy easing. Indeed, we believe that while inflation will pick up toward 3.5-4.0% y/y because of the tariffs, second round effects will be limited. Demand destruction from the tariffs along with pressures on employers to offset higher input cost will keep a lid on wages. For now, we maintain our baseline scenario of gradual policy easing. Our central case continues to anticipate three 25bps rate cuts in 2025, though we have shifted the timing of the first cut from June to July, with the remaining two expected in September and December. We emphasize that postponing the initial rate cut raises the risk that policymakers may need to accelerate the pace of easing later in the year to avoid falling behind the curve.

Edward Jones economist Mona Mahajan wrote in their recent weekly market wrap:

“We believe the decline in first-quarter GDP will likely reverse in Q2 as the huge surge in imports reverses in the weeks ahead, bringing second-quarter GDP to a positive figure. More broadly, we would expect U.S. GDP growth to soften this year from the 2.8% annual growth rate in 2024. In a base case — where tariffs remain around 10% or less with most trading partners, elevated in key sectors and negotiated somewhat lower with China — we would expect GDP growth to be in the 1.5% range this year. However, there is a tail risk that tariffs remain elevated across key trading partners and particularly with China. In this case, we could see a mild recession emerge, as inflation rises and consumption cools. However, we would not expect a deep or prolonged recession, particularly as the Fed may be able to lower interest rates more meaningfully. In either tariff scenario, growth may rebound in 2026 if the Fed is able to cut rates in the back half of 2025 and progress is made on tax reform and deregulation. This should support both consumer and corporate spending broadly.”

And while Mona laid out the risk of a recession, I also thought this chart was interesting. They highlighted that the overall expectation for corporate earnings growth in 2025 is still 9.5%, and that historically if earnings growth is positive we have not experienced recessionary environments in the US.

We have already seen meaningful downward revisions to the second quarter, as well as lowered expectations for Q3 and Q4. The expectation for corporate earnings growth for 2025 remains at about 9.5% annually. While this may be revised somewhat lower, historically, if earnings growth is positive, we have not experienced recessionary environments in the U.S.

And last but not least I wanted to close this out with a close up snapshot of some of the import surge we handled in Q1, courtesy of Joseph Politano . Why? Because I found it really interesting, and because it might explain any volumes carriers/brokers are experiencing if they are involved in these two sectors.

Joseph wrote:

Computers & pharmaceuticals were the two sectors behind the vast majority of that record import surge—outside those industries, the jump in imports was noticeable but not record-breaking. Pharmaceuticals, an industry Trump has long promised to hit with tariffs on but has exempted from nearly all trade policy actions so far, saw their real imports jump 60% from their previous record high. On the other hand, computers were not specifically targeted by Trump in the same way as pharmaceuticals during Q1, but they were heavily dependent on a Chinese & broader East-Asian supply chain that risked heavy disruption from tariffs. Real imports of laptops, desktops, and other computers thus rose by more than 50% in Q1 2025 as companies tried to prep for disruptions to their complex supply chains.

According to Joseph, these goods were stockpiled, and inventories are currently elevated. And, he even said he would expect further surges of imports in these sectors in Q2.

I’ll close out our Economics portion with Joseph’s closing thoughts on the current US economy:

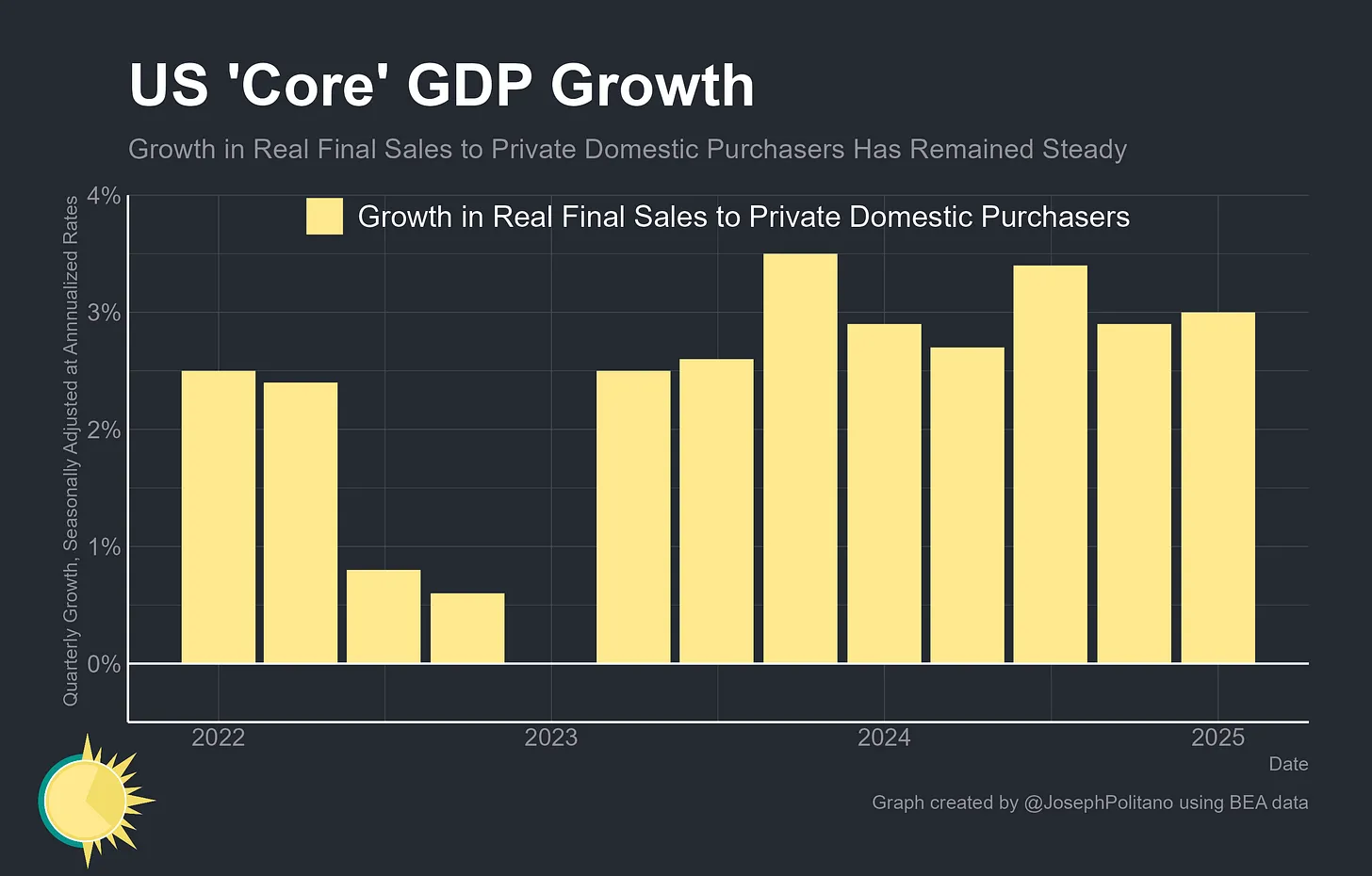

Yet even amidst all of this chaos, “core” American economic growth has held up relatively normally. Real final sales to private domestic purchasers—a mouthful of a term that just represents the sum of private-sector consumption & fixed investment—grew at a standard rate of 3%. These metrics are not wholly untainted by the effects of trade policy (the increase in fixed investment is mostly from tariff-driven computer imports, for example), but provide evidence that the economy has not yet entered a recessionary spiral. Going forward, volatility in overall GDP will be extra high given the wild swings in imports and inventories, so keeping an eye on the health of these “core” metrics will be critical.

A huge thank you to BiggerPicture for sponsoring this month's newsletter! BiggerPicture is focused on helping shippers, brokers, and carriers maximize their operational productivity, by reducing the time spent scheduling appointments by an average of 80%. Achieve full ROI in 3 months or less, and unlock new growth potential by shifting your most valuable resources (your peoples' time) where it can make the biggest impact.

More information on the announced deal with Britain:

President Trump announced on Thursday that the United States intended to sign a trade deal with Britain that would bring the two nations closer and roll back some of the punishing tariffs he issued on that country’s products. Both sides consider a trade pact deeply beneficial, and a deal has been under discussion since Mr. Trump’s first term. But the announcement on Thursday was scant on details, reflecting the haste of the Trump administration’s efforts to negotiate with more than a dozen nations and rework the global trading system in a matter of months. The agreement, which Mr. Trump said would be the first of many, would include Britain dropping its tariffs on U.S. beef, ethanol, sports equipment and other products, and buying $10 billion of Boeing airplanes. The United States in return said it would pare back tariffs that Mr. Trump has put on cars and steel, though it will leave a 10 percent levy in place for all British exports. Neither government has said when they expect the agreement to be finalized. A document released by the Trump administration on Thursday evening listed half a dozen general priorities, and said the countries would immediately begin negotiations “to develop and formalize” them.”

Cathy Morrow Roberson covered mentions of tariffs in earnings releases for Q1, and her full report is linked here to read.

Cathy quoted the CEO of Mattel, as saying:

“The combination of further diversifying our supply chain footprint and optimizing product sourcing and product mix is expected to reduce our U.S. imports from China to less than 15% of global production by 2026 and less than 10% by 2027, with additional contingency plans to accelerate that if required. Ynon Kreiz - Chairman & CEO. Q1 was not impacted by tariffs. We don't expect Q2 to be impacted. It's really in Q3 that we expect to see some tariff impact coming through as it works through the inventory of cycles. In terms of magnitude, the situation is very fluid, and a lot of uncertainty around the macroeconomic environment. Ynon Kreiz - Chairman & CEO.”

I felt this was significant because it shows the ongoing efforts supply chains have been making to diversify out of China. It also shows that tariffs might not have as big of an immediate impact on US inflation. Other companies cited attempting to mitigate or prevent any inflationary impacts to consumers in Q2. I would guess the extent of the impact of tariffs on inflation will more show in Q3 and Q4, and the magnitude of the impact likely could still be influenced by how quickly negotiations wrap up and the results of those negotiations.

While there has been a LOT of uncertainty straining markets because of tariffs, I can at the least say I might be grateful that we are getting it all done in “one go”. I know, we might feel otherwise right now, but the hope is that the end of 2025 and moving into 2026 will bring with it some certainty that allows for corporations to make and execute plans for growth.

Time will tell.

I’m keeping this section really simple this month, mostly because there is not much difference to note. It’s not a pretty picture. Remember normal seasonality should still be at play, and we should prepare for some summer seasonality trends in the market.

I’m also curious if the reports of the major import drops at the ports right now will turn drayage carriers into the regionalized full truckload markets, injecting some temporary capacity surplus. Something to consider.

Thank you to Ken Adamo at DAT for providing the updated charts!

Meet Me For Coffee with Samantha Jones seeks to correlate macro-economics to freight markets (just like this Newsletter does) and offers a chance to hear various industry and non-industry experts explain their thoughts on economics and freight markets.

Check out our Channels on your preferred platforms!

Thank you so much for reading and supporting the Truckload Market Update Report, produced by Samantha Jones Consulting LLC. Samantha Jones Consulting focuses on helping companies in the logistics industry better brand and sell their services to create sustainable revenue growth, and support their company growth goals!

We love Feedback, if you have questions, comments, suggestions, or are interested in sponsorships or partnerships, please email samantha@connectsjc.com to connect!

Make sure you subscribe to the Newsletter to receive the monthly update, and please share this with a friend who can also benefit from reading! As always, Samantha's work is free and created with the intent to add value to the transportation industry.